An artist talk “On Digital Colonialism and Monstrosity” by Morehshin Allahyari, followed by a discussion about “Iran’s modern art” moderated by Yasaman Tamizkar.

What happened…

“Art as a Form of Activism” was the third instalment of our event series about “Middle Eastern Women”, held at See You in Iran Cultural House on the evening of the October 4th. For the first part of the event Morehshin Allahyari, a new media artist joined us via Skype. Morehshin (born in 1985 in Tehran) is an artist, activist, educator and curator living in the United States who uses computer modelling, 3D scanning and printing, and digital fabrication techniques to explore the intersection of art and activism.

In the opening of her talk, Morehshin said she wants to focus on three major long term projects that she had been working on for the last 5 years, and reflects on poetic and practical possibilities of technology, re-figuration, digital colonialism, monstrosity, and myth-thinking as major concepts for these projects. The main question is How can we use technology as a tool for political resistance? For personal and collective storytelling; for defining space and opening up potentials?

Art activism is not about merely criticizing the art system or the general political and social conditions under which this system functions. But rather it’s about wanting to change the political, social, economical, and cultural conditions by means of art. Six years ago she got fascinated by the 3D printer and its potentials as a tool for creative thinking and resistance. In 2014, she started a collaboration with artist/writer Daniel Rourke in which they asked two main questions as a point of departure: what does a radical use of digital technology look like? What is radicality in this very time?

Only in recent years this technology has become available and affordable, so different companies, artists, etc. can own and use it. Around the time that there was a lot of hype around this technology, and lots of designers, artists, architects, and Silicon Valley companies were using it, she found their use super banal, boring and not critical. So she wanted to push the boundaries and discover new possibilities with this technology.

Between 2014 and 2017 they worked on two projects called the “3D Additivist Manifesto” and the “3D Additivist Cookbook”. They also coined the term “Additivism” which is a combination of two words “additive” and “activism”. We should think about Additivism as ways that through micro actions we can have macro influence; or build a community and collective around us which can re-think ways that we can work with or use this technology. The Manifesto that was published in 2015 calls for designers, writers, artists, technologists, etc. to participate in this project in relationship to this concept of Additivism.

She stressed that they were very focused on this idea of additive because there are additive processes; for example, 3D printing is an additive process because it prints something layer by layer and creates the final product. It is in contrast of carving which is a subtractive process. For 2 years they worked on works of different artists, designers and writers in forms of .obj and .stl files which are standard 3D printable files, and collected them in the “3D Additivist Cookbook” that includes 100 works of art and contains recipes, blueprints, essays, fictional stories, and an archive of .obj and .stl files. The material in the cookbook is open, free and available to all.

Around the same time, this video of ISIS destroying artifacts at Mosul museum came out and went viral, and it was a big shock to historian and archaeologists specially in the Middle East. In response to that video, Morehshin wanted to work on a project that sort of reconstructs these now destroyed artifacts. She gathered information and used 3D modelling technology to 3D print these artifacts. She modelled these pieces from the scratch due to lack of photos of them. Because the research part of this project became so important, she wanted to include those researches in the final work. So, inside the body of each artifact she embedded a flash drive and memory card that contains all the research, information and material she had gathered; meaning that anyone who can access these USBs, can recreate the 3D printed artifacts. This way these body of works will be preserved for the future generations; just like time capsules.

Around 2015-2016 there were a lot of tech-companies based in San Fransisco and Silicon Valley that were doing similar projects in reconstructing these artifacts, and there were lots of problems in the way that they were using this technology. They go to different parts of the Middle East or Africa, and they 3D scan these historical artifacts or sites, bring it back and have the copyright ownership of these data, and make profit off of selling these 3D models. That is when she came up with the term “Digital Colonialism”.

Digital colonialism is a framework for critically examining the tendency for information technologies to be deployed in ways that reproduce colonial power relationships. For example, for the past decade there has been this battle between Egyptian and German governments, where the Egyptians want back the Nefertiti bust, only to the Germans denial; despite the fact that it was brought to Germany without Egypt’s permission. New Museum in Berlin is also selling 3D printed replicas of the Nefertiti’s bust on their website for 8900 Euros, which are very accurate copies of the original sculpture because they have access to high-tech HD 3D scanners and printers. Morehshin showed a video of the mayor of London in 2016 launching a replica of Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph which was destroyed by ISIS in Syria. The narrative surrounding this story is how British saved this monument by reconstructing it and they became the heroes in this war. The problem with this is that they completely removed themselves from the fact that their politics were involved in the war in Iraq and Syria which in so many ways caused the formation of ISIS in the first place. So we could say part of the blame of destruction of the artifacts lays on the U.S. and other Western countries. “ISIS reclaims the object’s through destruction/through creating absence. The western governments and tech companies reclaim it after destruction, through a new kind of presence. And we fail to see the violence of that presence in the way we see the violence of the absence”.

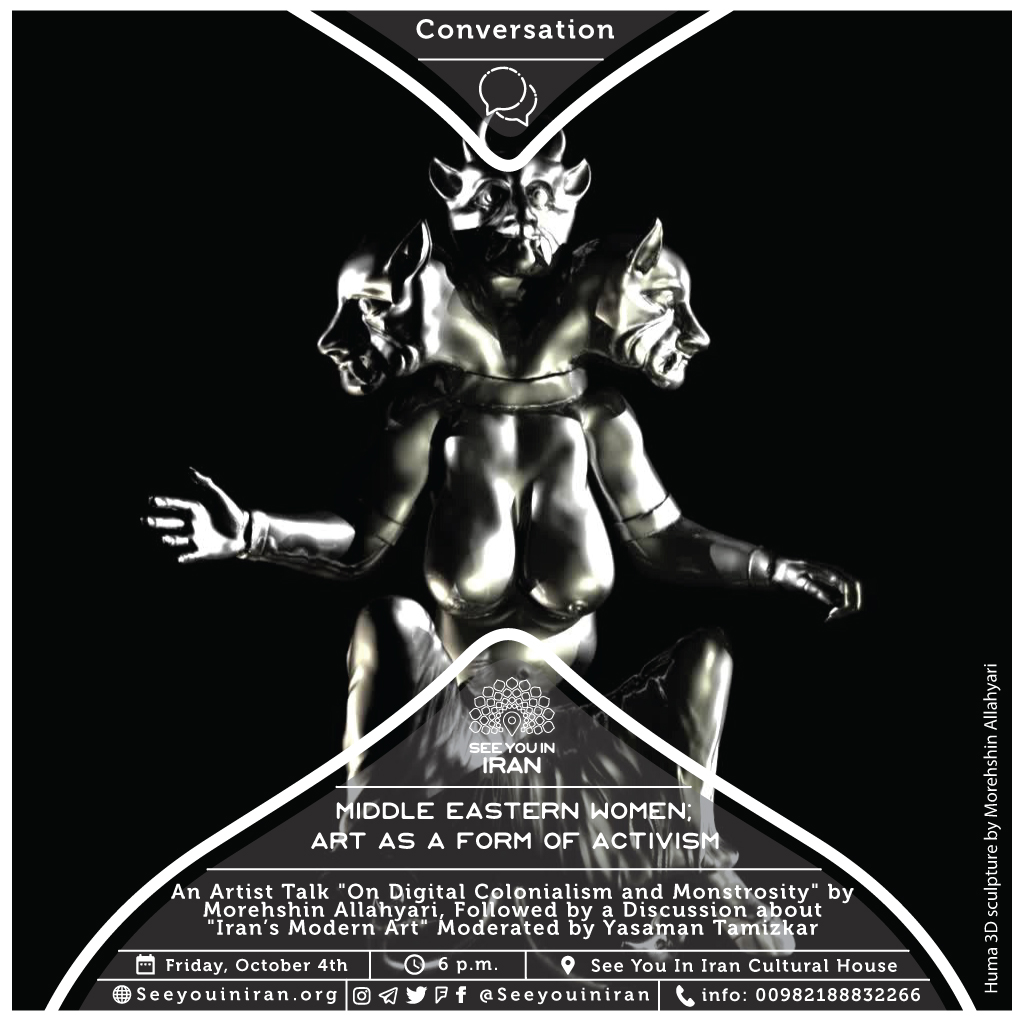

Her current project is “She Who Sees the Unknown” which is about different female or genderless monstrous figures of the Middle East and North Africa. The superheroes all over the world are dominantly male figures, but in old stories you can find these female monstrous figures that are powerful and beautiful with very empowering stories that are not represented these days. She wanted to go back, find these figures, then re-appropriate them and tell new stories about them based on whatever power they used to have, and then connect them to something in relationship to present or future. She was also fascinated by the figure of Jin that has the power to obey or disobey and has a hybrid human-monster quality to it.

Morehshin was also interested in the act of re-figuring as an activism and decolonizing practice. Through re-figuring – going back and taking something from the past that is misrepresented – we can tell new stories. Re-figuration can become a space for activation of different other spaces.

Then Morehshin proceeded to talk about different monstrous female Jins that she worked on (Huma, Aisha Qandisha, Ya’jooj Ma’jooj and the Laughing Snake) and how she re-appropriated them, their powers and the myth around them, in a way that enabled her to address modern issues and questions such as global warming, heartbreak and emotional healing, anti-emigration policies, sexual harassment, women’s agency over their body and collective experience of women in the Middle East.

She concluded her talk by saying that for her using technology in a poetic way has been an empowering position, especially where a lot of art-tech spaces are dominated by white men.

In the Q&A session one of the audience asked Morehshin about her concept of “digital colonialism” while he thought it may be more about conserving the cultural heritage rather than colonizing it. Morehshin answered that the companies doing these conservatism and 3D printing projects have the opportunity to make their data and information available to the locals to whom the artifacts and sites belong, and teach them how to conserve these heritages using 3D technology themselves, but they refuse to do so.

In the second part of the evening, audience gathered to talk about the “Impacts of Orientalism on Iran’s Contemporary Art and Artists” moderating by Yasaman Tamizkar, an art graduate and curator based in Tehran. Yasaman posed some questions like How would an Iranian Artist summarize the Middle Eastern/Iranian culture into an image? How much can we rely on that image to recall an identity? What element/object/concept/incident represents a culture in the best way? And who is telling our story? And how much can we rely on a “single story” on any subject?

To answer these questions, Yasaman started with her own take on the subject and said the hegemony that lies within the art world cues artists to reflect on issues that the Middle East has been dealing with for decades. Thus, artists are encouraged to create artworks that amplifies social conventions, rituals and any familiar image for the market, with the promise to be recognized in the competitive international art scene regardless of their country’s political reputation. The dangers of this situation – a desperation to impress the art market – is when a country, a culture or a social identity is defined by that one image. That image is not the whole truth. In fact, the truth is not the glamorous eye-catching social conventions and rituals, nor the dark side of political social limitation. The truth lies within the intersection of both interpretations. She said using symbols and elements which are believed to define our culture – but are expired symbols that were repeatedly used to shape (mis)conceptions of eastern societies through the lens of an outsider – in a form of art can make the art piece exotic. Then Yasaman showed some slides representing what she believed as “exotic art” and “orientalist view” of Iranian artists, one example of which could be “Chador Art”.

One of the audience believed that we can further the discussion based on the School of the Saqqaghaneh. Following the steps of artists like Tanavoli and Arabshahi who were prominent Saqqaghaneh artists in the 1960s, others wanted to reproduce exotic and west favourite arts that sells good at auctions; arts that have roots in religion and eastern cultures. In creation of these art works, art auctions and biennials’ dictations have a much greater role than creativity. Another member of the audience recalled the time she was invited to curate a global exhibition originated in Jordan. Queen Rania who was the force behind this exhibition wanted to name it “Breaking the Veils: Women Artists from the Islamic World”. It was very problematic because it wanted to have the stereotypes confirmed for the audience, that veils need breaking, instead of asking what is the veil. She thought part of this phenomenon is because the world we’re living in is so noisy that in order to be heard, you need to speak this language of codes and brands, and if you are an artist who doesn’t use these brands (like Chador or veil), you may go unrecognized. Another perspective discussed the relationship between capitalism and art production in today’s world and how market mechanisms are shaping the art scene in Iran.

Photos: Amin Behmanesh

رویداد سوم از سلسله رویدادهای زنان خاورمیانه با عنوان «هنر به مثابه کنشگری» در خانهی فرهنگی See You in Iran برگزار شد. در بعدازظهر ۱۲ مهر ابتدا از طریق اسکایپ میزبان مورهشین اللهیاری، هنرمند رسانههای جدید بودیم. مورهشین اللهیاری متولد ۱۳۶۴ تهران و هنرمند، کنشگر، مربی و کیوریتور ساکن ایالات متحده است که از مدلسازی کامپیوتری، اسکن و پرینت ۳بعدی و تکنیکهای ساخت دیجیتال برای برقراری رابطه میان هنر و کنشگری استفاده میکند. مورهشین در آغاز سخنرانیاش گفت میخواهد به سه پروژهی مهمی بپردازد که در پنج سال اخیر روی آنها کار کرده و دربارهی پتانسیلهای شاعرانه و عملگرایانهی تکنولوژی، باز–پیکربندی، استعمار دیجیتال، هیولاوارگی، و تفکر اسطورهای صحبت کند که اصلیترین مفاهیم موجود در این سه پروژه بودهاند: پرسش اصلی آن است که ما چطور میتوانیم از تکنولوژی به عنوان ابزاری برای مقاومت سیاسی، برای داستانگویی فردی و جمعی، و برای باز کردن فضا استفاده کنیم؟

کنشگری هنری تنها به نقد نظام هنری یا نقد وضعیت سیاسی و اجتماعی که این نظام بر مبنای آن کار میکند خلاصه نمیشود، بلکه به این معناست که بخواهیم شرایط سیاسی، اجتماعی، اقتصادی و فرهنگی را به وسیلهی هنر تغییر دهیم. او شش سال قبل مجذوب پرینتر ۳بعدی و قابلیتهایش به عنوان وسیلهای برای مقاومت و تفکر خلاق شد. در سال ۲۰۱۴ با همکاری هنرمند/نویسندهی بریتانیایی دنیل رورک پروژهای هنری را آغاز کرد و در آن دو پرسش اساسی را نقطهی حرکت خود قرار داد: استفادهی «رادیکال» از ساخت نمونههای بدلی دیجیتال به چه شکل است؟ و در دنیای امروز، رادیکال بودن به چه معناست؟

تنها در سالهای اخیر است که این تکنولوژی با قیمت نسبتا پایین در دسترس همه قرار گرفته، و کمپانیها، هنرمندان و طراحان مختلف میتوانند از آن به راحتی استفاده کنند. در همان زمان که تب استفاده از این تکنولوژی داغ بود و طراحان، هنرمندان، معماران و کمپانیهای سیلیکونولی در پروژههایشان از آن استفاده میکردند، از نظر مورهشین شکل استفادهی این افراد از فناوری سه بعدی به شدت مبتذل، ملالآور و غیرنقادانه بود. لذا او میخواست این محدودیتها را به چالش بکشد و امکانات و قابلیتهای جدید و متفاوت این تکنولوژی را کشف کند.

بین سالهای ۲۰۱۴ تا ۲۰۱۷ آنها بر روی دو پروژهی «مانیفست افزودگر ۳بعدی» و «کتاب آشپزی افزودگر ۳بعدی» کار کردند، و همچنین عبارت «افزودگری» را ابداع کردند که از ترکیب دو واژهی «افزودنی» و «کنشگری» حاصل شده است. برای درک عبارت افزودگری باید به آن به عنوان راهی برای تاثیرگذاری کلان از طریق کنشهای خُرد، یا ساخت اجتماعی در اطرافمان نگاه کرد که میتواند راههایی نوین برای بهره گیری از این تکنولوژی را ابداع کند. مانیفست ۳بعدی که در سال ۲۰۱۵ منتشر شد از طراحان، نویسندگان، هنرمندان، فنآوران و دیگران دعوت کرد در رابطه با مفهوم «افزودگری» در این پروژه مشارکت کنند.

مورهشین تاکید کرد علت تمرکزشان بر روی ایدهی افزودنی، وجود فرایندهای مختلف افزودنی بود؛ مثلا میتوان گفت پرینت ۳بعدی یک فرایند افزودنی است چون این فناوری یک شی خاص را لایه لایه پرینت کرده و به محصول نهایی شکل میدهد. این درست برعکس مثلا حکاکی است که یک فرایند کاهنده محسوب میشود. آنها به مدت ۲ سال بر روی آثار هنرمندان، طراحان و نویسندگان مختلف در فرمتهای .obj و .stl (که فایلهای مناسب برای پرینت ۳بعدی هستند) کار کرده و آنها را در «کتاب آشپزی افزودگر ۳بعدی» جمع کردند که شامل ۱۰۰ اثر هنری است و مجموعهای از دستورالعملها، طرحها، مقالات، داستانهای تخیلی، و آرشیوی از فایلهای obj. و stl. را در خود جای داده است. اطلاعات و منابع موجود در کتاب آشپزی باز، رایگان و برای همه قابل دسترسی است.

در همان زمان بود که ویدئویی از داعش در حال تخریب آثار باستانی در موزهی موصل منتشر و بسیار فراگیر شد و تاریخدانان و باستانشناسان را علیالخصوص در خاور میانه در بهت و حیرت فرو برد. در پاسخ به این ویدئو، مورهشین تصمیم به کار روی پروژهای گرفت که به نوعی به بازسازی این آثار تخریب شده میپرداخت. او به جمع آوری اطلاعات دربارهی این آثار پرداخت و با استفاده از تکنولوژی مدلسازی ۳بعدی، آنها را پرینت ۳بعدی کرد. به علت کمبود عکس و تصویر از این آثار باستانی، مورهشین مجبور شد آنها را از ابتدا طراحی و مدلسازی کند. از آنجا که بخش پژوهشی این پروژه از اهمیت زیادی برایش برخوردار بود، تصمیم گرفت به نحوی این تحقیقات را در اثر نهایی بگنجاند. بنابراین در بدنهی هر اثر، کارت حافظهای قرار داد که شامل تمام اطلاعات، دادهها و منابعی بود که برای کار جمعآوری و تولید شده بودند و این به آن معنا بود که هرکس به این کارت حافظه دسترسی داشته باشد میتواند آن اثر باستانی را پرینت ۳بعدی کند. به این ترتیب این آثار هنری درست مانند کپسول زمان برای نسلهای آینده حفظ میشوند.

در حدود سالهای ۲۰۱۵ و ۲۰۱۶ کمپانیهای فناوری فراوانی در سانفرانسیسکو و سیلیکونولی روی پروژههای مشابه بازسازی آثار باستانی کار میکردند؛ اما شیوهی استفادهشان از این تکنولوژی با ایرادات متعددی همراه بود. چنین شرکتهایی به بخشهای مختلف خاورمیانه و آفریقا میروند و این آثار و اماکن تاریخی را اسکن ۳بعدی میکنند، آنها را به کشور خود میآوردند، از حق مالکیت معنوی دادههای به دست آمده برخوردار میشوند و از فروش مدلهای پرینت ۳بعدی بهرهی مالی میبرند. در مواجهه با این مساله بود که مورهشین عبارت «استعمار دیجیتال» را مطرح کرد.

استعمار دیجیتال چارچوبی برای بررسی نقادانهی گرایش به بهرهگیری از تکنولوژیهای اطلاعاتی به روشهایی است که روابط قدرت استعماری را بازتولید میکنند. مثلا در طول یک دههی گذشته میان دولتهای آلمان و مصر بر سر مجسمهی سر نفرتیتی مجادله بوده و علیرغم این واقعیت که این مجسمه بدون رضایت و اجازهی مصر به آلمان آورده شده، دولت آلمان از بازپسدادن آن به مصر امتناع میکند. حتی «موزهی جدید» برلین مجسمههای پرینت ۳بعدی سر نفرتیتی را به قیمت ۸۹۰۰ یورو بر روی وبسایت خود بفروش میرساند. به علت دسترسی گردانندگان موزه به پرینتر و اسکنرهای ۳بعدی فوق حرفهای و باکیفیت، این نسخههای بدلی، کپی بسیار دقیقی از مجسمهی اصلی هستند. مورهشین ویدئویی از شهردار لندن در سال ۲۰۱۶ را نشان داد که در حال رونمایی از کپی طاق نصرت پالمیرا (که در سوریه به دست داعش تخریب شد) در یکی از میدانهای لندن است. روایت موجود حول محور این ماجرا میگوید چطور بریتانیا این اثر باستانی را از طریق بازسازیاش حفظ کرد و به قهرمان جنگ تبدیل شد. مشکل آنجاست که در این روایت بریتانیا خود را کاملا از این واقعیت مبری میکند که تاثیر سیاستهایش در جنگ در عراق و سوریه به دلایل گوناگون موجب شکل گیری داعش شده است. بنابراین میتوان گفت که در ماجرای تخریب آثار باستانی، بخشی از تقصیر متوجه آمریکا و کشورهای غربی است. «داعش اشیا باستانی را از طریق نابودی/ غیبت از آن خود کرد. دولتهای غربی و شرکتهای فناوری بعد از نابودی اشیا، آنها را از طریق نوع جدیدی از حضور از آن خود کردند. و ما از دیدن خشونت موجود در این «حضور» ناتوانیم (برعکس آنکه که میتوانیم به راحتی خشونت موجود در غیبت را ببنیم)».

پروژهی فعلی مورهشین با عنوان «او که ناشناخته را میبیند» دربارهی شمایلهای مونث یا بیجنسیت هیولاواری است که ریشه در اسطورههای خاورمیانه و شمال آفریقا دارند. در اکثر نقاط دنیا ابرقهرمانها شمایلهایی با جنسیت مذکرند، اما میتوان در داستانهای قدیمی ردپای این شمایلهای مونث هیولاوار را مشاهده کرد که قدرتمند و زیبا هستند و داستانهای توانمندکنندهای دارند که امروز از روایتها حذف شده است. مورهشین میخواست به گذشته برود، این شمایلها را بیابد، آنها را باز–از–آن–خود سازد و بر اساس قدرت منسوب به هر شمایل داستانهای جدید دربارهشان بگوید، و سپس آنها را به امری در ارتباط با حال یا آینده مرتبط سازد. او همچنین مجذوب شمایلهای جن شد که قدرت اطاعت یا سرپیچی دارند و به نوعی موجودی دورگه انسان–هیولا هستند.

همچنین مورهشین به کنش باز–پیکربندی به عنوان نوعی کنشگری و عمل ضداستعماری نگاه میکند. با عمل باز–پیکربندی – رفتن به پس و برگزیدن چیزی از گذشته که تحریف شده – میتوانیم داستانهای جدید بگوییم. باز–پیکربندی میتواند به فضایی برای فعالسازی فضاهای متفاوت دیگر تبدیل شود.

در ادامه مورهشین دربارهی چند شمایل مونث و هیولاوار جن صحبت کرد (حوما، عیشه قندیشه، یاجوج و ماجوج و مار قهقهه) و اینکه چطور توانسته این شمایلها، قدرتشان و اسطورهیشان را به ترتیبی باز–از–آن–خود سازد که بتواند به وسیلهی آنها به مسائل و پرسشهای امروزی بپردازد؛ مسائلی نظیر گرمایش زمین، دلشکستگی و التیام احساسی، سیاستهای ضد مهاجرت، آزار جنسی، عاملیت زنان بر بدنشان و تجربهی مشترک زنان در خاورمیانه.

مورهشین در پایان، سخنرانیاش را با ذکر این نکته به پایان برد که استفادهی شاعرانه از تکنولوژی برایش این دستاورد را داشته که او را در موقعیتی توانمندشده قرار داده؛ بخصوص در زمانی که فضای هنری–فناوری در سیطرهی مردان سفید پوست است.

در بخش پرسش و پاسخ، یکی از حاضران دربارهی مفهوم «استعمار دیجیتال» سوال کرد و معتقد بود اسکن ۳بعدی آثار باستانی توسط شرکتهای فناوری، نه عملی استعماری بلکه کاری در راستای حفظ این آثار است. مورهشین گفت کمپانیهایی که پروژههای حفاظتی و پرینت ۳بعدی انجام میدهند این امکان را دارند که دادهها و اطلاعاتشان را در اختیار افراد محلی و کشوری قرار دهند که آن اثر باستانی در آن قرار دارد، و حفظ این آثار با استفاده از تکنولوژی ۳بعدی را به آنها آموزش دهند، اما از این کار امتناع میکنند.

در بخش دوم رویداد، حاضران در بحث گروهی پیرامون موضوع «تاثیر اورینتالیسم بر هنر و هنرمندان معاصر ایران» شرکت کردند که با هدایت یاسمن تمیزکار، کیوریتور و دانشآموختهی هنر مستقر در تهران صورت گرفت. در ابتدا یاسمن سوالاتی را مطرح کرد از جمله چطور یک هنرمند ایرانی میتواند فرهنگ خاورمیانه/ایران را در یک تصویر خلاصه کند؟ چقدر میتوانیم برای فراخوانی یک هویت، به آن تک تصویر تکیه کنیم؟ چه المانها/اشیا/مفاهیم/حوادثی به بهترین شکل نمایندهی یک فرهنگند؟ چه کسی راوی داستان ماست؟ و چقدر میتوانیم دربارهی هر موضوعی تنها بر «یک روایت» تکیه کنیم؟

در پاسخ به این پرسشها، یاسمن دیدگاه و موضع خود را بیان کرد و گفت هژمونی موجود در دنیای هنر، هنرمندان را به سمت پرداختن به مسائلی سوق میدهد که خاورمیانه دهههاست با آنها دست به گریبان است. در نتیجه هنرمندان تشویق به خلق آثاری میشوند که در آنها آیینها و رسوم اجتماعی و در واقع هر تصویر آشنایی برای بازار با شدت بیشتری به نمایش در میآیند؛ با این وعده که فارغ از وضعیت سیاسی کشورشان، در فضای هنری رقابتی بینالمللی مورد توجه قرار بگیرند. خطر چنین وضعیتی – استیصال و نیاز به تحت تاثیر قرار دادن بازار هنر – آنجاست که یک کشور، فرهنگ یا هویت اجتماعی تنها با آن تک تصویر تعریف شود. آن تصویر تمام واقعیت نیست؛ بلکه حقیقت نه رسوم و آیینهای زیبا و چشمگیر است و نه وجههی تاریک محدودیتهای سیاسی اجتماعی. حقیقت جایی میان این دو تفسیر نهفته است. استفاده از نمادها و المانهایی که به معرفهای فرهنگ ما بدل شدهاند – اما در واقع نمادهای تاریخ گذشتهای هستند که مکررا برای شکل دهی به مفاهیم جوامع شرقی از چشم یک خارجی مورد استفاده قرار گرفتهاند – در یک اثر هنری، موجب میشود آن اثر وجههای اگزاتیک به خود بگیرد. سپس یاسمن تصاویری از آثار هنری را نشان داد که به عقیدهی او نمایشگر «هنر اگزاتیک» و «دیدگاه اورینتالیستی» هنرمندان ایرانی بود (مانند «هنر چادر»).

در ادامه، یکی از شرکت کنندگان به مبحث مکتب سقاخانه اشاره کرد. از نظر او در ادامهی موفقیت هنرمندانی نظیر عربشاهی و تناولی که از سردمداران مکتب سقاخانه در دههی ۱۳۴۰ بودند، دیگران نیز میخواستند همان هنر اگزاتیک و موردپسند غرب را بازتولید کنند که در حراجیها خوب میفروخت؛ هنری که ریشه در مذهب و فرهنگ شرقی داشت. در خلق این آثار هنری، دیکتهی حراجیهای هنری و بینالها نقش بسیار پررنگتری از خلاقیت بازی میکنند. یکی دیگر از حاضران خاطرهای را نقل کرد که از او دعوت شده بود کیوریتوری یک نمایشگاه هنری بینالمللی را در اردن به عهده بگیرد. ایدهپرداز اصلی این نمایشگاه ملکه رانیا بود که در نظر داشت عنوان آن را «شکستن حجاب: زنان هنرمند از جهان اسلام» بگذارد. چنین عنوانی بسیار مساله ساز بود چرا که میخواست بر کلیشههای ذهنی مخاطبان صحه بگذارد: «بجای آن که از چیستی حجاب بپرسیم، باید آن را بشکنیم»! این مخاطب معتقد بود یکی از دلایل این پدیده آن است که دنیای امروز بسیار شلوغ و پر سر و صداست و برای شنیده شدن، باید به زبان این کدها و برندها حرف زد، و اگر شما هنرمندی هستید که از این برندها (نظیر چادر و حجاب) در آثارتان استفاده نمیکنید، احتمالا دیده نخواهید شد. از دیدگاهی کلانتر یکی از مخاطبان دربارهی رابطهی میان سرمایهداری و تولید هنر در دنیای امروز صحبت کرد و اینکه چطور ساز و کارهای بازار به فضای هنری ایران شکل میدهند.

عکس: امین بهمنش

What to expect

In the third event of the “Middle Eastern Women” event series, we will focus on art and artists. Morehshin Allahyari, an Iranian artist and activist living in the US gives an artist talk about the relationship between colonialism, patriarchy and digital technologies, activism and re-figuring ancient figures in her talk “On Digital Colonialism and Monstrosity”. Then we will have a conversation and discuss the impacts of neo-colonialism on modern art in Iran and the Middle East, moderated by Yasaman Tamizkar, art graduate and curator. Join us for “Middle Eastern Women; Art as a Form of Activism” event on Friday, October 4th at 6 p.m. at See You in Iran Cultural House.