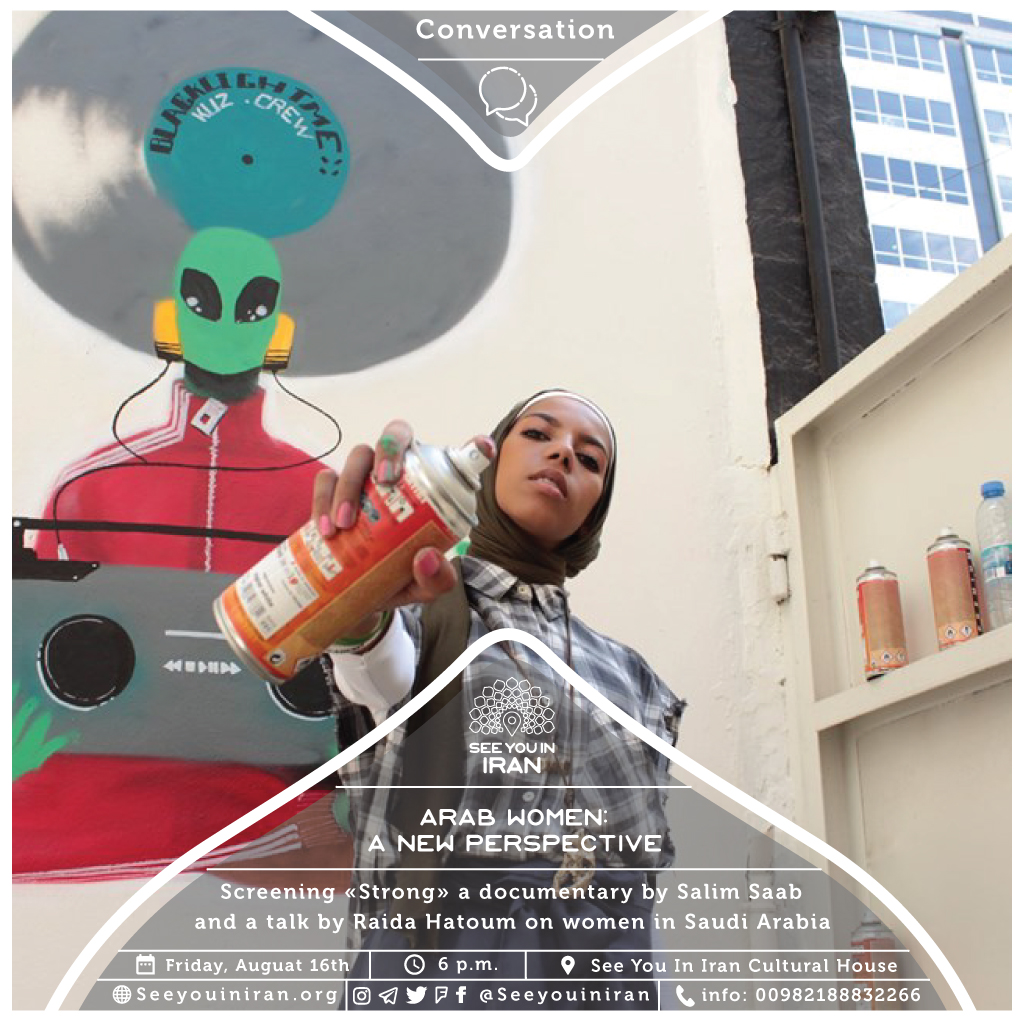

Screening “Strong” a Documentary by Salim Saab and a Talk by Raida Hatoum on Women in Saudi Arabia

What Happened …

“Arab Women: a New Perspective” was the second event from the event series about “Middle Eastern Women” that took place on August 16th at the See You in Iran Cultural House. In the first part of the evening, the short documentary “Strong” was shown which was directed by Salim Saab in 2018. Salim is a Franco-Lebanese former rap artist, movie director, radio host and journalist who to break the stereotypes about Arab women, tells the story of eight female artists that express themselves through unconventional arts such as hip hop، graffiti، tattoo and even martial arts. Each of these women fearlessly talks about her art, inspirations, everyday life and even her views on feminism. Most of these artist are based in Lebanon but there are some women represented in the film from Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia. Artists featured in “Strong” are Abrar Allahou (graffiti artist), Hanan Kamal (graffiti artist), Krystelle Harb (dancer), Lana Ramadan (hiphop and martial arts artist), Lili Ghandour (singer and hiphop dancer), Marie Joe Ayoub (graffiti artists), Marwa El Charif (tattoo artist) and Nawel Ben Kraiem (singer). In the film, Lili Ghandour a hip hop artist and singer says: “There are a lot of people here that think I’m crazy, like in a bad way, you know? But that is okay, people are afraid of change. If they see any change, they get scared. If they see someone who’s different, it’s not in their comfort zone, it’s not in their safety zone, and they get scared. That’s okay, let them be scared, let them get out of their bubble”. The screening started after an exclusive video message from Salim who introduced himself and his work to the Cultural House’s audience.

After the screening, Raida Hatoum talked about women’s situation in Saudi Arabia in her talk titled “I am my own guardian”. Raida is a Lebanese activists working in Lebanon; but she was born and lived in Saudi Arabia until her late 20s. Living there made her aware of women’s issues in SA, so upon going back to Lebanon she joined a grassroots Palestinian feminist group and later started to work for international organizations. She is working with women movements, anti-racism and anti-sectarianism groups for more than 18 years. She introduces herself as an activists in fields of socioeconomic justice and gender equality.

Raida started her talk with the fact that all of us in the different countries of the region are having unrealistic and stereotypical images of each other. But we should be aware that we share a same future and fate and we must work together to shape this future by challenging these stereotypes, regardless of borders, politics or physical distances. Whatever happens in one country will affect other countries, and whatever happens to the women of one country, will affect women in other countries of the region. For example when in the late 1970s the Islamic Republic of Iran was announced, Saudi Arabia imposed numerous restrictions over women’s activities and public presence just to promote itself as the most devoted and best Islamic state in the Middle East.

In her introduction, Raida gave us a brief record of the political, economic and social situation of Saudi Arabia in the recent history. Politically, Malek Salman and his son Mohamad Bin Salman made MBS the crown prince using power and wealth in 2015. Economically, until 2015 Saudi Arabia used to be a welfare state with an oil based “centralized capitalist economy”, providing all kinds of free or cheap services to people. After 2015 and as a part of the MBS’ “Vision 2030”, he restructured the economy and tried to limit the reliance on oil money. As the result, public sector employees’ wages – which constituted about tow third of all employees – dropped dramatically. In essence, SA was on its way to privatize public sector and impose taxes on services, in order to move from a “centralized capitalism to a liberal capitalism”.

In terms of social transformation, before 1980s women used to work in agriculture in rural areas. Access to education was limited for girls and most of the education they received was in the informal classes held under the trees. In urban areas, different social groups (Saudis, Arabs, Asians, Africans, Iranians, and of course Europeans and Americans who were called foreigners) lived and worked side by side. Text books at school were full of Gnostic texts and TV channels showed Lebanese musicals with women dancing in mini-skirts. Girls’ right to education was stated in the law and no man could prevent females in his family from seeking education. Saudi families used to picnic at parks, and women could go camping and swimming with their families or female friends. Even though education was free for all regardless of gender, the government provided assistance for only men to find a job in the public sector. Until 1980s and establishment of the moral police, women had access to almost all public places. But in 80s police started to investigate the relationship between men and women in public spaces, and arrest men if they were not related to the women they were accompanying.

From 1980s to 2015, SA became a “Wahabbi Islamic kingdom” and along with it gender segregation in the public space, media censorship and patrolling the streets by the moral police became a normal habit in the society. Although women’s access to education was still intact, they were denied from working in public places such as restaurant, and even from attending government-run gyms and sport facilities. Women needed their male guardian’s permission to get married, get divorced, get a passport, travel abroad, start a business or even get a job, and they did not have any political rights. Saudi women were second degree citizens whose lives were controlled by their male relatives. Even though about 60 percent of college graduates were women, they only constituted about 13 percent of the workforce. About one third of private businesses were owned by women, but they legally needed a male manager at their business (Raida pointed out that in recent years, the government has allowed mixed gender concerts, women driving, women participating in elections and sport events, and the male guardianship system has been abolished and women – over 21 years old – can work or travel abroad without needing their guardian permission).

After this detailed introduction, Raida talked about Arab Spring and how that echoed in Saudi Arabia as well, but international and regional media that are sponsored by SA did not cover the events. Yet from 2011 to 2014 social activists used social media to organize and mobilize social forces. Raida proceeded to recount the main women movements in Saudi Arabia. One of the most important movements was about abolishing the male guardianship system. Wajeha Al-Huwaider is a prominent activist who fought against this law since 2003. In 2016 “I am my own guardian” campaign started and 2500 women sent telegraph to Malek Salman and 14700 more signed a petition to abolish this system. The other campaign was about the right to vote and it was known as “Balady” or “My Country”. After women’s widespread activism in 2011, the ban on women’s participating and voting in elections was lifted. The third movement was about women’s right to drive that went viral with #women2drive. Although women had struggled for years to achieve this right, in 2011 and following the Arab Spring, they were again encouraged to resume their activities, and lots of women filmed themselves driving in the street and shared the videos online. Lots of these women were arrested, but in 2017 this ban was finally lifted.

From 2015 until today, there has been sever oppression in the country and MBS arrested several other princes (who may have claim over the thrown), writers, journalists and women activists. In May 2018 in a massive crackdown, 17 activists were arrested. Most of these people were released on bail after one year but three still remain in jail. In 2019, 13 other social and women activists were arrested.

An interesting point in Raida’s talk was about society’s reaction to these developments. Although a majority of the people were supportive of these activisms, some people rejected them and some even started violent confrontation; men would chase female drivers or call for killing women without proper hijab. But with no doubt the harshest reactions were against abolishing the male guardianship system. “The movement also is faced by a pro-regime women movement, supporting the state’s reforms yet opposing the right-based independent women movement”.

An important part of Raida’s talk was dedicated to the recent social reforms by Mohamad Bin Salman in Saudi Arabia. In her opinion these reforms are part of the MBS’ “Vision 2030” and are in reality part of International Monetary Fund’s privatization plans. In order to make SA a modern Islamic state, MBS imposes some hand-picked reforms, and at the same time oppresses all activists and liberation seeking movements. MBS is is after modernizing the society with a top down approach, and by oppressing any right-based movements, he wants to have control over all parts of culture and society; he wants to be able to deny what he gave as soon as he wants to. MBS, like many other states in the region, uses and misuses women’s rights to promote a modern image of the Saudi government, and does this in a complete agreement with the international community and its double standards; as SA elected to be a member of the UN women’s rights commission in 2017.

At the end of the evening and after Raida introduced a number of the Saudi women activists and the prices they paid for their activism, some of the audience members (including audience from Iran, Turkey and France) talked about their shared experiences and found remarkable similarities between women’s movements in their countries and in Saudi Arabia.

Photos: Amin Behmanesh – Navid Assadi Khomami

رویداد دوم از سلسله رویدادهای زنان خاورمیانه در روز ۲۵ مرداد با موضوع «زنان عرب: نگاهی تازه» در خانهی فرهنگی See You in Iran برگزار شد. در بخش اول این رویداد، فیلم «قویه» محصول ۲۰۱۸ به کارگردانی سلیم صعب به نمایش درآمد. سلیم خوانندهی سابق رپ، کارگردان، مجری رادیو و روزنامهنگار لبنانی–فرانسوی است که برای شکستن کلیشههای رایج دربارهی زنان عرب، به سراغ هشت زن هنرمند میرود که افکار و احساساتشان را از مسیر هنرهایی نظیر هیپهاپ، گرافیتی، خالکوبی و حتی ورزشهای رزمی ابراز میکنند. هر یک از این زنان بدون واهمه علایق، هنر، زندگی روزمره و حتی دیدگاهشان نسبت به فمینیسم را بازگو میکنند. بیشتر این هنرمندان در لبنان مشفول به کار و فعالیتند اما هنرمندانی از کویت، عربستان سعودی و تونس نیز به تصویر کشیده شدهاند. هنرمندان حاضر در فیلم شامل ابرار اللهو، حنان کمال, کریستال حرب، لنا رمضان، لیلی غندور، مری–جو ایوب، مروا الشریف و نوال بنکریم میشود. در بخشی از فیلم، لیلی غندور هنرمند هیپهاپ میگوید: «خیلی از مردم اینجا فکر میکنند من دیوانهام! اما اشکالی نداره، مردم از تغییر میترسند. اگر تغییری ببینند، وحشت میکنند. اگر آدم متفاوتی ببینند، احساس ناخوشایندی بهشون دست میده و میترسند. ولی اشکالی نداره، بگذار بترسند. بگذار مجبور شن از این حباب بیان بیرون». نمایش این فیلم با پیام ویدئویی اختصاصی سلیم صعب برای مخاطبان خانهی فرهنگی که در آن به معرفی خود و کارنامهاش میپرداخت همراه بود.

در ادامهی رویداد، رائده حاطوم در سخنرانی خود با عنوان «من قیم خودم هستم» دربارهی وضعیت زنان عربستان صحبت کرد. رائده فعال اجتماعی لبنانی و ساکن لبنان است که در عربستان به دنیا آمده و تا اواخر دهه ۲۰ زندگی خود در این کشور زندگی کرده. زندگی در عربستان رائده را با مسائل و مشکلات زنان آشنا کرد و به همین دلیل در بازگشت به لبنان به یک سازمان فمینیستی مردمنهاد فلسطینی ملحق شد و سپس به سازمانهای بینالملی پیوست. رائده بیش از ۱۸ سال است با جنبشهای زنان و گروههای ضدنژادپرستی و ضدفرقهگرایی همکاری دارد. او خود را فعال حوزهی عدالت اقتصادی-اجتماعی و برابری جنسیتی میداند.

رائده صحبتهای خود را با این واقعیت آغاز کرد که همهی ما در کشورهای مختلف منطقه، درگیر تصاویر کلیشهای و نامطبق با واقعیت از یکدیگریم و باید متوجه باشیم که همگی آینده و سرنوشت مشترکی خواهیم داشت و برای شکل دادن به این آینده، باید فارغ از مرز و سیاست و فاصله و با به چالش کشیدن این کلیشهها در کنار یکدیگر همکاری کنیم. هر اتفاقی که در یک کشور بیافتد، کشورهای دیگر را نیز تحت تاثیر قرار میدهد و هر اتفاقی برای زنان یک کشور بیافتد، زنان دیگر کشورها نیز متاثر میشوند. مثلا وقتی در اواخر دههی ۷۰ میلادی جمهوری اسلامی ایران موجودیت خود را اعلام کرد، عربستان سعودی محدودیتهای متعددی برای زنان اعمال کرد تا تصویر عربستان را به عنوان «اسلامیترین» حکومت منطقه تثبیت کند.

رائده در مقدمهی صحبتهایش ابتدا تاریخچهای از وضعیت سیاسی، اقتصادی و اجتماعی عربستان ارائه داد. از نظر سیاسی در سال ۲۰۱۵ ملک سلمان و پسرش شاهزاده محمد بن سلمان با خشونت و بهرهگیری از قدرت و ثروت، محمد بن سلمان را به مقام ولیعهدی رساندند. از نظر اقتصادی تا پیش از ۲۰۱۵ عربستان دولت رفاهی بود که با یک اقتصاد سرمایهداری متمرکز مبتنی بر نفت، خدمات رفاهی به مردم ارائه میداد. بعد از ۲۰۱۵ به عنوان بخشی از «چشمانداز ۲۰۳۰» بن سلمان برای ساختاربندی دوباره اقتصاد و فاصله گیری از درآمدهای نفت، دست مزد شاغلان بخش عمومی که برابر با دو سوم کل شاغلان است را به شدت کاهش داد. در حقیقت عربستان در مسیر خصوصی سازی بخش عمومی و اعمال مالیات بر خدمات و تبدیل از یک سرمایهداری متمرکز به سرمایهداری لیبرال قرار گرفت.

از نظر اجتماعی، تا پیش از دهه ۱۹۸۰ زنان در مناطق روستایی با لباسهای محلی به کار و فعالیت کشاورزی مشغول بودند. دسترسی دختران به آموزش محدود بود و غالب آموزش به صورت غیررسمی و در سایهی درختان صورت میگرفت. در مناطق شهری اجتماعات و گروههای مختلفی در کنار یکدیگیر زندگی میکردند (سعودیها، اعراب، آسیاییها، آفریقاییها و ایرانیها، و البته اروپاییها و آمریکاییها که خارجی نامیده میشدند).

در کتب درسی آموزههای متعدد عرفانی به چشم میخورد و تلویزیونی برنامههای موزیکال لبنانی با رقصندههای زن پخش میکرد. حق تحصیل زنان در قانون تصریح شده بود و هیچ مردی نمیتوانست جلوی تحصیل زنان خانوادهاش را بگیرد. یکی از تفریحات خانوادههای سعودی، پیک نیک در پارکها بود و زنان با خانواده یا گروههای زنانه به کمپ، شنا و تفریح میرفتند. هرچند تحصیل در دانشگاه برای زنان و مردان رایگان بود، دولت برای اشتغال مردان در بخش عمومی تسهیلات بیشتری فراهم میکرد. زنان تا دههی ۸۰ و پیش از استقرار پلیس اخلاقی به غالب فضاهای عموم دسترسی داشتند، اما پس از آن گشتهای پلیس به بررسی حجاب زنان و روابط بین زن و مرد پرداخته و در صورت تخلف، مردان راهی زندان میشدند.

از دههی ۸۰ تا سال ۲۰۱۵، عربستان به یک پادشاهی اسلامی وهابی تبدیل شد و همراه با آن جداسازی جنسیتی، سانسور رسانهها و گشتهای خیابانی به مسائل عادی جامعه تبدیل شد. هرچند هنوز دسترسی زنان به آموزش به قوت خود باقی بود، دسترسی آنان به شغلهایی که لازمهاشان کار در فضای عمومی بود (سوپرمارکت، رستوران) و حتی ورزشگاهها و باشگاههای دولتی ممنوع شد. زنان برای ازدواج، طلاق، دریافت گذرنامه، سفر خارجی، تاسیس کسب و کار یا اشتغال به اجازهی قیم مرد خود نیاز داشتد و از هیچ گونه حقوق سیاسی برخوردار نبودند. در حقیقت زنان عربستان به واسطهی جنسیتشان از حقوق انسانی محروم شده و به عنوان شهروندان درجه دویی شناخته شدند که خویشاوندان مرد آنها کنترل زندگی روزمرهیشان را در دست داشتند. اگرچه ۶۰ درصد فارغالتحصیلان دانشگاههای عربستان زنانند، آنها تنها ۱۳ درصد نیروی کار کشور را تشکیل میدهند. حدود یک سوم بخش خصوصی در مالکیت زنان است اما مدیریت این کسب و کارها قاونونا باید مرد باشد. (رائده یادآوری میکند که طی سالهای اخیر اجازهی برگزاری کنسرتهای عمومی مختلط، رانندگی زنان، شرکت زنان در انتخابات و رویدادهای ورزشی آزاد شده، نظام قیمومت ملغی شده و زنان بالای ۲۱ سال میتوانند بدون اجازهی قیم خود کار، سفر و ازدواج کنند).

در ادامه رائده به انقلابات موسوم به بهار عربی اشاره کرد و گفت اگرچه این جنبشها در عربستان سعودی نیز رخ داد، اما رسانههای بینالمللی و منطقهای که عربستان حامی مالیشان است، این رویدادها را پوشش ندادند. با این حال از سال ۲۰۱۱ تا ۲۰۱۴ فعالان اجتماعی و آزادیخواهان با استفاده از رسانههای اجتماعی به سازماندهی و بسیج نیرویهای اجتماعی پرداختند. رائده در سخنرانی خود اصلیترین محورهای جنبشهای زنان در عربستان را برشمرد. مهمترین محور، لغو نظام قیمومت مردان بر زنان است. فعال سرشناس در این حوزه وجیهه الوحیدر است که از سال ۲۰۰۳ برای الغای نظام قیمومت تلاش میکند. در سال ۲۰۱۶ کمپین «أنا ولية أمري» یا «من قیم خودم هستم» به راه افتاد که طی آن ۲۵۰۰ زن به ملک سلمان پیام دادند و ۱۴۷۰۰ نفر دیگر نیز درخواست الغای این قانون را امضا کردند. کمپین دیگر، حق رای دادن زنان است که با عنوان «بلدی» یا «کشورم» شناخته میشود. بعد از مبارزات زنان در سال ۲۰۱۱، محدودیت شرکت و رای دادن در انتخابات برای زنان برداشته شد. مورد سوم، کمپین رانندگی زنان است که با هشتگ #women2drive فراگیر شد. اگرچه زنان سعودی سالها برای بازپس گیری این حق مبارزه کردند، اما در سال ۲۰۱۱ و گسترش بهار عربی، زنان نیز تشویق شدند فعالیتهای خود را از سر بگیرند و زنان بسیاری فیلم رانندگی خود در خیابانها را در رسانههای اجتماعی به اشتراک گذاشتند و البته بسیاری از این فعالان نیز دستگیر شدند. در نهایت در سال ۲۰۱۷ این محدودیت برداشته شد.

از سال ۲۰۱۵ تا به امروز خفقان شدیدی در کشور حکمفرما شده و بن سلمان به سرکوب شاهزادهها، نویسندهها، روزنامه نگاران و فعالان زنان پرداخته است. در ماه مه سال ۲۰۱۸ در سرکوبی گسترده و هماهنگ ۱۷ نفر از فعالان مدنی دستگیر شدند. بیشتر این افراد پس از یک سال به قید وثیقه آزاد شدند ولی سه نفر هنوز در بازداشتند. در سال ۲۰۱۹ نیز ۱۳ فعال اجتماعی و زنان دیگر بازداشت شدند.

واکنش جامعه به این جنبشها از حمایت تا ترد و تا مقابلهی فیزیکی را شامل میشد؛ از مردانی که زنان راننده را دنبال میکردند یا خودرویشان را به آتش میکشیدند، تا افرادی که در شبکههای اجتماعی خواستار قتل زنان بیحجاب میشدند. ولی بیتردید شدیدترین واکنشها نسبت به الغای قانون قیمومت مردان بود. همچنین جنبش زنانِ همرای حکومت نیز شکل گرفت که موافق اصلاحاتِ از بالای بن سلمان، ولی مخالف جنبشهای مستقل مبتنی بر حقوق بشر بود.

بخش مهمی از سخنان رائده به اصلاحات محمد بنسلمان اختصاص داشت. به نظر او این اصلاحات از «چشمانداز ۲۰۳۰» بن سلمان نشات میگیرند که در واقع در راستای هماهنگی با برنامههای خصوصی سازی صندوق بینالمللی پول است. بن سلمان برای تبدیل عربستان به یک حکومت اسلامی مدرن، دست به اصلاحات محدود در کنار سرکوب گسترده زده است. بن سلمان به دنبال مدرن کردن از بالای جامعه است و با سرکوب جنبشهای مبتنی بر حقوق بشر، در پی کنترل تمام جوانب فرهنگ و جامعه است؛ او میخواهد اگر روزی آزادیای به شهروندان میدهد، روز دیگر بتواند آن را دریغ کند. بن سلمان مانند بسیاری از کشورهای دیگر منطقه، و با همدستی جامعهی جهانی و استانداردهای دو گانهی آن، از حقوق زنان برای ارائهی تصویری مدرن از حکومت سعودی استفاده و سوءاستفاده میکند؛ چنانکه عربستان سعودی در سال ۲۰۱۷ به عضویت کمیسیون مقام زن ملل متحد درآمد.

در پایان برنامه و پس از معرفی برخی از فعالان زن سعودی توسط رائده, تعدادی از حاضران از جمله مخاطبانی از ایران، ترکیه و فرانسه با مقایسه و یافتن تشابهات قابل توجهی میان جنبشهای زنان در کشور خود و عربستان سعودی، پرسشها خود را مطرح کردند.

عکس: امین بهمنش – نوید اسدی خمامی

What to Expect

What is our image of an Arab woman? How accurate is this image? How much mainstream media has affected our perception? Although women in different parts of the Middle East share a same background and history, face the same challenges in gaining freedom and human rights, and struggle with the same regional and international oppressive forces, each one goes through a unique lived experience, has her own sets of interests and inspirations, and has her distinctive contribution to the world.

.

In the second event of the “Middle Eastern Women” event series, we talk about Arab women. Together we will watch “Strong”, a documentary by Lebanese/French director Salim Saab about a group of Saudi and Lebanese women challenging their conservative society’s norms through their art. Then Raida Hatoum, a Lebanese activist who was born and raised in Saudi Arabia will talk about women’s situation in Saudi Arabia, the challenges they face and their achievements in a speech titled “I am my own guardian”. Join us for “Arab Women: a New Perspective” event on Friday August 16th at 6 p.m. at See You in Iran Cultural House