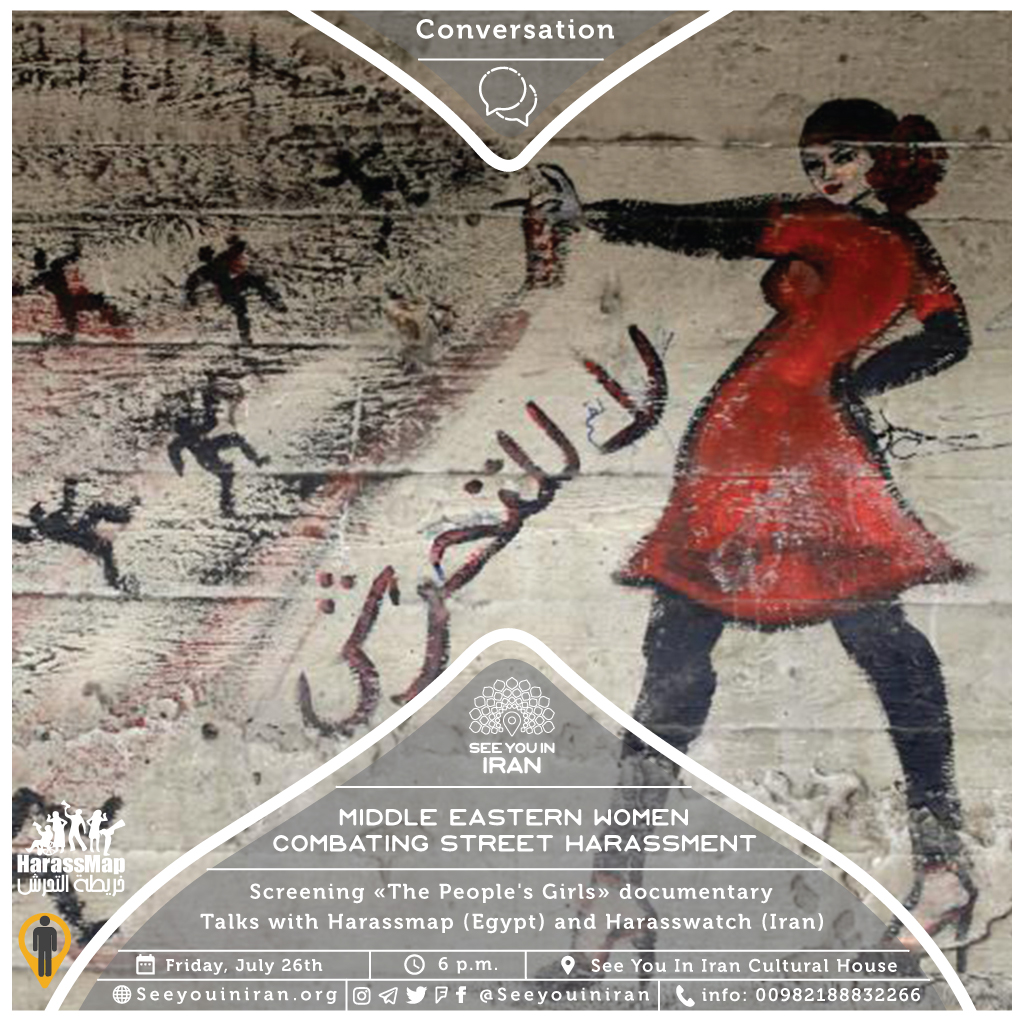

Screening “The People’s Girls” documentary, following with talks with Harassmap (Egypt) and Harasswatch (Iran) founders.

What Happened …

“Combating Street Harassment” was the first event of our event series about Middle Eastern Women and it was held in the See You in Iran Cultural House on Friday July 26th. First part of the evening was dedicated to the screening of the short documentary “The People’s Girls” which explores sexual and street harassment in Egypt, its causes, victims and women’s experiences, and the different tactics they employ to combat harassment. Next was the speech by Rebecca Chiao, one of the founders of “HarassMap” organization who joined us via Skype. She gave an introduction about HarassMap, their innovative software for reporting sexual/street harassments, different approaches towards combating harassment and empowering women, and their achievements during these past years. Then she answered audience’s questions. In the third part of the evening, members of HarassWatch who fight against street harassment in Iran took the stage and gave a detailed account of their activities, harassment victim’s narratives and different approaches to fight against harassment, and in the end they answered the questions raised during the Q&A.

FIRST PART: The event began with the screening of “The People’s Girls” (2016). After two years of living in Egypt and experiencing harassment in the streets of Cairo, Colette Ghunim and Tinne Van Loon decided to make a documentary about this pervasive problem in Egypt. Tinne Van Loon is an American-Belgian photographer and filmmaker based in Cairo who in her work addresses social issues about Middle Eastern communities, especially Middle Eastern Women’s problems. Colette Ghunim is also an independent American-Arab filmmaker who met Tinne while she was studying abroad at the American University of Cairo in 2013. In 2014 they made “Creepers on the Bridge”, a short video that showed the haunting stares of sexual harassers in Cairo’s streets. The video went viral and women from around the world made their own version of it. Colette and Tinne decided to have a closer look to Egypt in 2016 and they started shooting The People’s Girls using crowdfunding. In this short documentary, the filmmakers join a group of volunteers to ask male passer-by what are the motives behind harassment? Almost every answers revolved around the way women dress. The film follows psychological, social and family related factors associated to harassers’ actions. Then, different women who experienced harassment tell their stories and we realize even wearing niqab or veil does not protect them from harassment. In the second part of the film, the directors explore different tactics to fight against harassment including physical confrontation, spreading awareness using social media, and the most important of all, responding and speaking up to the harasser at the time of incident and calling them out.

SECOND PART: In the second part of the event Rebecca Chiao one of the founders of HarassMap joined us via Skype, and Farid translated her talk into Persian. Rebecca was born and raised in the United States. After a trip to the Occupied Territories and witnessing Israeli oppression against the Palestinian people, she felt compelled to challenge injustice and decided to study International Development. She then went to Egypt and after noticing the intensity of sexual harassment in the streets, she decided to found HarassMap organization – an online platform for reporting incident of harassment from around the country – with the help of a team of volunteers. Rebecca explained that sexual/street harassment means anything from suggestive or threatening looks, to touching, to rape and finally to mob assaults where multiple attackers sexually assault one victim. The problem is so pervasive in Egypt that more than 99% of women had experienced it in their life time according to UNWomen in 2013. The organization’s approach is to decentralize and mobilize community action against harassment to change the social acceptability of harassing. HarassMap accepts anonymous reports of harassment, maps them online, and points victims to services. These reports will then turn into research data that help designing campaigns to encourage bystanders to take action and consequently making neighbourhoods safe for women.

In the past 10 years HarassMap had faced multiple challenges; since Egyptian revolution in 2011 different regimes (from Muslim Brotherhood to military government) took over the country with their own sets of laws and regulations, and each time HarassMap had to adapt its activities according to the new situation. But HM activities has had unforeseen impacts too, such as their contribution to breaking the taboo of admitting to being harassed by women, and also including the discussion about the issue into the public discourse. Moreover, a few months after the campaign started, a new law was passed addressing harassment. The unexpected participation of men and boys in the campaign was another promising aspect of working in the Egyptian society.

We then proceed to the Q&A session. The first critique was regarding gentrification of the areas that are perceived safer on the HarassMap (which are probably more prosperous neighbourhoods) and degradation of the already poor areas (in which harassment occurs more frequently). The critique suggested this process results in worsening the bad economic situation in these neighbourhoods. Rebecca believed: “Sexual harassment is so widespread in Egypt that almost all women and some men experience it constantly no matter where they are, so they don’t need a map really, they just expect it all the time”. Another question was looking at social and economic problems in Egypt in recent years, and the impact of sever poverty on unemployed and hopeless men. One of the audience asked if HarassMap activities make the already angry young men – who are themselves victims of the situation – more furious and hateful? Rebecca argued that there is no direct link between sexual harassment and economic situation, and men from different social classes harass women. This unfortunate epidemic was in place even before the economy stated to fall 8 or 9 years ago. Also HarassMap tries to be inclusive and treat people – of all social groups and classes – as problem solvers rather than the origin of problems.

THIRD PART: In the third part, Zarrin took the stage as a representative of HarassWatch and talked about the ideas behind establishing the group and their experiences in the past year. In their opinion, street harassment was a shared experience and everybody, regardless of their gender, race or class, need to participate in social dialogue to address this issue. Having said that, HarassWatch team talked with other activists from different countries – including HarassMap in Egypt – and after designing a number of educational posters, participated in their first civil activity on the streets of Tehran on March 8, 2018. They talked to metro commuters about experiencing harassment and the role of bystanders and witnesses, and distributed educational brochures. In summer 2018, they launched their website which demonstrates a map of harassment using anonymous reports. This map’s significances are to abolish class-based view towards harassment, and also help HarassWatch volunteers to have a bolder presence in the unsafe areas. Zarrin then continued her talk by reading through some of the victims and witnesses’ experiences who shared their narratives on the website.

Zarrin said it is more than one year that they go to the streets to distribute their posters and talk to shopkeepers, taxi drivers and other citizens in different provinces about urban safety. They also encountered a number of wrong common believes such as “some women enjoy being catcalled”, “if a woman doesn’t want to be catcalled, she would wear appropriate dresses in the public space”, or “nobody harass a veiled woman”. These examples show people think the way a woman dresses is the green light to harassment. Another wrong approach is looking at harassment as a class-based issue and lots of people think it only happens among lower social and economic classes. That is why HW decided to redirect part of its attention towards other public spaces such as universities, schools, and private and public companies. The other issue is that people recognize harassment only in its physical forms and they do not consider catcalling or inappropriate staring as harassment. A big problem in fighting against harassment in Iran is the police’s approach. Some police officers do not think of street harassment as a big deal, and sometimes blame the victim for the way she dressed.

In the Q&A session a member of the audience raised a question about the possibility of cooperation between HarassWatch and state agancies especially municipalities. Ghoncheh, another member of HW, said although there is no direct cooperation, municipality of Tehran once asked for permission to use HarassWatch posters and graphics in metro stations, and they did for a short period of time. Another Audience voiced her concern and said in her opinion HarassWatch’s activities will be focused only on middle-class women, and lower class women will be forgotten and excluded in these narratives, just like other social and feminist movements in Iran. Ghoncheh said: “including less privileged women in our activism was one of our priorities from the beginning. A majority of our work is on the streets, and by talking to people and distributing our brochures on metro stations and in the Grand Bazar, we try to address the issue in all social and economic classes. Another idea to address this weakness was to work with community centres, but since we don’t have authorization yet, we weren’t able to reach this goal”. The next question was about the scope of HW activities and if their work extends to men as well. “We ask our users to specify their gender (male, female or other) on the website” said Negin. She added: “But in order to be most effective in the society, we need to focus on the people that are dealing with this problem more severly (in this case women)”. Elaheh continued: “We received multiple reports from transgenders or adult men, but the majority of narratives are coming from women”. Another male member of the audience asked: “How can we show our support and protect the victims without being accused of patriarchal protective behaviours? I was even accused of planning to take advantage of the victim when I was trying to help her in a harassment incident”. Neging responded: “We always advise people to not get physical as long as possible, and employ other innovative approaches like distracting the harasser by asking a question, or blocking his way. Alternatively if we weren’t successful in preventing the harassment, we can help the victim call her relatives, or support her as a potential witness in case she decides to file a report with the police”.

CONCLUSION: Watching The People’s Girls documentary and listening to HarassWatch activists and Rebecca Chiao from HarassMap, it is evident that experiencing street harassment and the original causes behind it are mostly common in the different parts of the region. To combat this problem, there is a need for collective action with all people participating regardless of their ethnicity, gender or social class. Breaking the taboo of talking about harassment, raising awareness and educating people, changing social norms and a grassroots movement in addition to cooperation with different state agencies and NGOs can lead to a gradual and effective improvement in the society.

Photos: Mohamad Shaban

نمای کلی: اولین رویداد از سلسله رویدادهای زنان خاورمیانه با موضوع «مبارزه با آزار خیابانی» روز جمعه ۴ مرداد در محل خانهی فرهنگی See You in Iran برگزار شد. در این رویداد ابتدا فیلم مستند کوتاه «دختران مردم» به نمایش درآمد که در آن به مسالهی آزار جنسی و خیابانی در مصر، سر منشا این مشکل فراگیر، تجربیات زنان مصری و در نهایت روشهای مختلف مبارزهی آنها با آزار پرداخته شده است. در ادامه ربکا چاو، از بنیانگذاران سازمان «نقشهی آزار» HarassMap در مصر از طریق اسکایپ به جمع ما ملحق شد و بعد از معرفی فعالیتهای سازمان، نرم افزار ابداعی نقشهی آزار برای گزارش انواع آزار خیابانی و جنسی، روشهای توانمندسازی زنان و دستاوردهای نقشهی آزار، به سوالات تعدادی از حاضران پاسخ داد. در نهایت اعضای گروه «دیدهبان آزار» HarassWatch که در زمینهی مبارزه با آزار خیابانی در ایران فعالیت میکنند ابتدا توضیحات دقیقی دربارهی فعالیتهای گروه، روایتهای آزاردیدگان و شیوههای رویارویی با آزارگر ارائه دادند و در نهایت جمعی از افراد گروه به سوالات مخاطبان پاسخ دادند.

بخش اول: در آغاز برنامه فیلم «دختران مردم» (The People’s Girls, 2016) به نمایش درآمد. کولت غانیم و تین ونلون پس از دو سال زندگی در مصر و تجربهی آزار در خیابانهای قاهره تصمیم گرفتند فیلمی مستند و کوتاه دربارهی این مشکل فراگیر در مصر بسازند. تین ونلون فیلمساز و عکاس مستند آمریکایی–بلژیکی مستقر در قاهره است که در آثارش به مسائل اجتماعی نظیر اجتماعات خاورمیانه و بخصوص مشکلات زنان خاورمیانه میپردازد. کولت غانیم نیز فیلمساز مستقل آمریکایی–عرب است که در سال ۲۰۱۳ وقتی برای تحصیل به دانشگاه آمریکایی قاهره رفته بود، با تین آشنا شد. کولت و تین در سال ۲۰۱۴ ویدئوی کوتاهی به نام خزندگان روی پل (Creepers on the Bridge) ساختند و در آن تجربه یک روز خود در خیابانهای قاهره را در مواجهه با نگاهها و آزارهای مردان به نمایش کشیدند. این ویدئو در تمام دنیا سر و صدا کرد و زنان کشورهای دیگر نیز تجربیات خود را به تصویر کشیدند. در سال ۲۰۱۶ کولت و تین تصمیم گرفتند نگاه دقیقتری به مصر داشته باشند و به همین دلیل فیلم دختران مردم را با بهره گیری از امکان تامین مالی جمعی جلوی دوربین بردند. در این فیلم ابتدا فیلمسازان با گروهی از داوطلبان به میان مردان میروند و جویای علت آزار خیابانی و جنسی میشوند. تقریبا همه، نحوهی لباس پوشیدن زنان را علت اصلی آزار میدانستند. سپس عوامل روانی، خانوادگی و اجتماعی پشت اعمال آزارگر بررسی شد و در ادامه زنان مختلفی که مورد آزار قرار گرفته بودند از تجربیات خود گفتند. با شنیدن این روایتها متوجه میشویم حتی چادر و نقاب نیز آنان را از آزار مصون نگه نداشته است. در نیمهی دوم فیلم به روشهای مختلفِ مبارزه با آزار پرداخته میشود از جمله برخورد فیزیکی، آگاهی بخشی از طریق شبکههای اجتماعی و مهمتر از همه، مواجهه رو در رو و واکنش در لحظه به آزارگر.

بخش دوم: در بخش دوم ربکا چاو یکی از بنیانگذاران سازمان نقشهی آزار از طریق اسکایپ به ما پیوست و فرید، یکی از داوطلبان و همراهان همیشگی خانهی فرهنگی، صحبتهای او را برای حاضران ترجمه کرد. ربکا در آمریکا متولد و بزرگ شده و بعد از سفری به سرزمینهای اشغالی و مشاهدهی سرکوب فلسطینیان توسط اسرائیل، تصمیم میگیرد مبارزه با بیعدالتی را هدف اصلی خود قرار دهد و در نتیجه در رشتهی توسعهی بینالملل مشغول به تحصیل میشود. ربکا به مصر میرود و در پی آشنایی با وضعیت ناگوار آزار جنسی و خیابانی زنان در مصر، سازمان نقشهی آزار را با کمک جمعی از داوطلبان بنا میکند که در حقیقت ابزاری آنلاین است که موارد وقوع آزار در سرتاسر مصر در آن گزارش میشود. ربکا توضیح میدهد آزار شامل هر فعلی میشود که برای فرد دیگر ناخوشایند است؛ از نگاههای نامناسب و تهدیدآمیز گرفته تا لمس و تجاوز و در نهایت حملهی دسته جمعی. این مساله آنقدر در مصر شایع است که به گزارش سازمان زنان ملل متحد در ۲۰۱۳ بیش از ۹۹ درصد زنان تجربهی آزار را داشتهاند. رویکرد این سازمان مرکززدایی و بسیج اقدامات همگانی در مقابله با آزار به منظور تغییر نرمهای اجتماعی است. نقشهی آزار با دریافت گزارشهای مردمی، آنها را روی نقشهی آنلاین مشخص کرده و آزاردیده را به مراکز حمایتی راهنمایی میکند. در ادامه، این گزارشها به دادههای تحقیقاتی تبدیل میشوند که میتوانند در طراحی کمپینهایی برای تشویق شاهدان آزار به اقدام به عمل کمک کنند و به این ترتیب محلهها برای زنان امن شوند.

در طول ۱۰ سال فعالیت نقشهی آزار، این سازمان با چالشهای گوناگونی نیز روبرو بوده است. مثلا از انقلاب سال ۲۰۱۱ مصر تا بحال دولتهای گوناگونی بر سر کار آمدهاند (از اخوان المسلمین تا دولت نظامی) و هر کدام مقررات متفاوت و رورکردهای گوناگونی نسبت بع فعالیتهای نقشهی آزار اتخاذ کردهاند و بنیانگذاران سازمان هر بار ناچار به تطبیق با وضعیت جدید بودهاند. اما اقدامات این سازمان پیامدهای پیشبینی نشدهای نیز به همراه داشته است. مثلا شکسته شدن تابوی اعتراف به آزاردیدن از طرف زنان و ورود این بحث به گفتمان اجتماعی در سطح فرد، دولت و جامعه. همچنین با فاصلهی چند ماه از راه افتادن این کمپین، قانون جدیدی برای مبارزه با آزار تصویب شد. مشارکت مردانی که با علاقه در این کمپین شرکت میکردند نیز دستاورد غیرمنتظرهی دیگر بود.

سپس ربکا پاسخگوی سوالات حاضران بود. وی در پاسخ به نقدی دربارهی اعیانسازی معکوس مناطقی که تعداد گزارشهای آزار در آنها زیاد است و محرومیت بیشتر محلاتی که به احتمال زیاد همین حالا هم از محرومیت رنج میبرند گفت: «آزار جنسی آنچنان در مصر گسترده است که تقریبا تمام زنان و بخشی از مردان، فارغ از اینکه در چه شهر و محلهای باشند آن را تجربه میکنند. بنابراین افراد نیاز چندانی به این نقشه ندارند، بلکه تقریبا همواره و همهجا انتظار دارند مورد آزار قرار بگیرند». در پرسشی دیگر یکی از حاضران عنوان کرد که در سالهای اخیر جامعهی مصر با مشکلات اجتماعی و اقتصادی فراوان و فقر شدید دست به گریبان بوده و این مساله موجب شکل گرفتن خشم عمومی بخصوص در مردان میشود که بدون کار و امید به آیندهاند. چطور نقشهی آزار سعی میکند به نفرت و خشونت مردانی که خود قربانی شرایطند دامن نزند؟ ربکا معتقد بود آزار جنسی ربط مستقیمی به شرایط اقتصادی ندارد و مردان از تمام طبقات اجتماعی دست به آزار میزنند و این وضعیت حتی پیش از مشکلات و تغییرات جدید نیز وجود داشت. همچنین «کمپین ما تلاش میکند همه را در بر بگیرد و ما با مردم به عنوان حلال مشکلات و نه بانی مشکلات برخورد میکنیم و مخاطب خود را تنها گروه خاصی از مردم قرار نمیدهیم».

بخش سوم: سپس زرین به نمایندگی از گروه دیدهبان آزار از چرایی تشکیل این گروه و تجربههایشان از یک سال فعالیت حرف زد. به عقیدهی زرین آزار خیابانی یک تجربهی مشترک است و همه از هر طبقه و نژاد و جنسیت باید برای حل آن وارد تعامل و گفتگو بشوند. با این پیش زمینه گروه دیدهبان آزار با فعالان دیگر کشورها از جمله نقشهی آزار صحبت کردند و بعد از طراحی پوسترها، در روز ۸ مارس ۲۰۱۸ اولین فعالیت میدانی خودشان را انجام دادند. آنها با مسافران مترو دربارهی تجربهی آزار و نقش شاهد حرف زدند و بروشورهای آموزشی را میان مردم پخش کردند. در تابستان سال ۹۷ وبسایت راهاندازی شد که در آن نقشهای از گزارشهای مردمی دربارهی آزار وجود دارد. اهمیت این نقشه یکی از بین بردن تصویر طبقاتی نسبت به آزار است و دیگر آنکه به داوطلبان دیدهبان آزار که در سطح شهر حضور دارند کمک میکند حضور پر رنگتری در مناطق ناامنتر داشته باشند. سپس زرین تعدادی از روایتهای افراد آزار دیده و شاهدان آزار را که تجربهی خود را در سایت ثبت کرده بودند برای حاضران خواند.

زرین گفت حالا بیشتر از یک سال است که برای پخش کردن پوسترهای منع آزار به خیابان میروند و با مغازهدارها، رانندههای تاکسی و شهروندان دیگر در استانهای مختلف در مورد امنیت شهری صحبت میکنند. آنها در این مدت با باورهای رایج غلطی نیز مواجه شدند؛ «بعضی زنها از شنیدن متلک خوششان میآید»، یا «اگر کسی نخواهد چیزی بشنود با لباس مناسب در خیابان ظاهر میشود» یا «کسی با زنان محجبه کاری ندارد» و این باورها به معنای آن است که برای مردم پوشش افراد مجوز آزار خیابانی است. باور غلط دیگر طبقاتی دیدن آزار است و بسیاری از مردم معتقدند مزاحمت خیابانی تنها محدود به اقشار فرودست اقتصادی و اجتماعی میشود. به همین منظور گروه دیدهبان آزار توجه خود را بعد از خیابان معطوف به اماکن عمومی دیگر نظیر دانشگاه، ادارات و مدارس کردهاند. مسالهی دیگر باورهای رایج در مورد مصادیق آزار جنسی است که بیشتر مردم آزار را تنها در اشکال فیزیکی آن به رسمیت میشناسند و ایرادی در متلک و نگاه نامناسب نمیبینند. یکی دیگر از مشکلات مبارزه با آزار در ایران، رویکرد پلیس است که در مواردی بعضی ماموران آزار خیابانی را موضوع چندان مهمی نمیبینند یا قربانی را بواسطهی شکل حجابش سرزنش میکنند.

در بخش پرسش و پاسخ، در پاسخ به سوالی دربارهی همکاری دیدهبان آزار با ارگانهای دولتی و بخصوص شهرداریها، غنچه (از پایهگذاران گروه) عنوان کرد اگرچه همکاری مستقیمی وجود ندارد، اما شهرداری تهران با آنها تماس گرفته و درخواست کرده پوسترهایشان را در ایستگاههای مترو نصب کند که این کار با موافقت گروه دیدهبان آزار برای مدت کوتاهی عملی شد. یکی از حاضران نقدی وارد کرد مبنی بر اینکه به عقیدهی او «این فعالیت نیز همانند سایر فعالیتهای مربوط به حوزهی زنان، به طبقهی متوسط محدود خواهد شد و طبقهی فرودست مثل همیشه فراموش شده و کنار گذاشته میشوند، که اتفاقا مساله آزار در این طبقه به هیچ عنوان کمرنگ نیست. شما برای دخیل کردن زنان طبقهی فرودست در این روایتها چه کاری انجام دادهاید»؟ غنچه در پاسخ گفت «یکی از دغدغههای ما حتی قبل از راه اندازی وبسایت همین مساله بود. از آنجا که بخش مهمی از کار ما میدانی است، وقتی در مترو یا بازار بزرگ با مردم صحبت میکنیم و جزوهها را پخش میکنیم، به این ترتیب تقریبا به تعامل با تمام طبقات پرداختهایم. ایدهی دیگر برای جبران این ضعف، ورود به سرای محلهها است ولی هنوز به علت عدم صدور مجوز موفق به این کار نشدهایم». در پاسخ به سوال یکی آقایان حاضر در جمع که آیا کار این گروه تنها به زنان محدود میشود یا به مردان نیز گسترش پیدا میکند؟ نگین پاسخ داد «در سایت بخشی برای تعیین جنسیت فرد آزاردیده یا شاهد مشخص شده و در محتوای علمی–پژوهشی خود نیز به این مساله میپردازیم. اما گاهی مجبوریم بیشتر انرژی و تمرکز خود را روی بخشی بگذاریم که مشکل حادتر است و در این مورد آزار زنان در فضای عمومی شایعتر است». الهه در تکمیل حرفهای نگین گفت گزارشهای زیادی از افراد تراجنسی و مردها دریافت کردهاند ولی خوب اکثر روایتها مربوط به زنان است. یکی دیگر از آقایان این سوال را مطرح کرد که «چطور میتوان در حمایت از فرد آزاردیده ظاهر شد بدون آنکه متهم به غیرتمندی و ناموس پرستی شویم، چون گاهی پیش آمده که وقتی در مقام دفاع از زنی برآمدهام متهم شدهام که خودم میخواهم با او دوست شوم». نگین گفت «ما همیشه پیشنهاد میکنیم که تا جای ممکن از مداخله فیزیکی اجتناب کنید و از راههای دیگری وارد شوید مانند پرت کردن حواس آزارگر با پرسیدن یک سوال یا قرار گرفتن در مسیر آزارگر. یا اگر در جلوگیری از آزار موفق نبودیم میتوانیم به قربانی کمک کنیم با آشنایانش تماس بگیرد یا اگر برای شکایت نیاز به شاهد دارد به عنوان شاهد حاضر شویم».

جمعبندی: مشاهدهی فیلم دختران مردم و شنیدن صحبتهای ربکا چاو از نقشهی آزار و فعالان گروه دیدهبان آزار نشان داد تجربهی آزار خیابانی و دلایل وقوع آن تقریبا در نقاط مختلف منطقه یکسان است و مقابله با آن نیازمند یک کنش جمعی و همکاری و همراهی تمام مردم یک جامعه فارغ از قومیت، جنسیت و طبقه است. در این راه شکستن تابوی صحبت دربارهی آزار، آموزش و آگاهسازی افراد، تغییر هنجارهای اجتماعی و حرکت از پایین به بالا از متن جامعه در کنار همکاری سازمانها دولتی یا مردمنهاد دیگر میتواند به تغییرات گام به گام و موثر در جامعه منجر شود.

عکاس: محمد شعبان

What to Expect

Lots of women in the world have experienced street harassment; but this disturbing encounter has become an inevitable and daily routine for a lot of women in some parts of the Middle East. According to UN Women, 99.3 percent of women participating in a survey in Egypt in 2013 reported experiencing at least one type of sexual in their lifetime. In “The People’s Girls” documentary, Colette Ghunim and Tinne Van Loon went to the streets of Cairo to answer the question of who is to blame for street harassment? Women wearing provocative dresses? Or men thinking harassing women is their right? Or families reproducing patriarchal norms in upbringing their children?

In our first event of “Middle Eastern” event series, we will have a conversation about street harassment. After screening “The People’s Girls”, we are hosting founders of HarassMap (Egypt) and HarassWatch (Iran) to share their narratives and experiences about combating sexual and street harassment. Join us for this event on Friday July 26th at 6 p.m. at See You in Iran Cultural House.

Photo: graffiti in Cairo