“How to talk about gender-based violence?” is a 2016 article by Nadje Al-Ali, professor of gender studies at SOAS. Although her work in analyzing approaches towards violence has wildly been based on the context of Iraq, she believes that the case is relevant for other Middle Eastern countries as well. In this article Dr. Al-Ali points to the importance of avoiding dichotomous approaches in terms of the macro and micro power configurations that intersect and are constitutive of each other, but that can never be reduced to one or the other. For example, in the case of 2016 Iraq, it was not just ISIS that played a role in committing gender-based violence, but also the western occupation, various Iraqi governments and their militia, insurgents and sectarian groups, armed gangs, and individual family members have all been perpetrators of the most vile forms of gender-based violence, ranging from domestic violence, verbal and physical intimidation, sexual harassment, rape, forced marriage, trafficking, forced prostitution, female genital mutilation, and honour-based crimes, including killings.

She argues that among the west scholars, the tension is often reduced to explanatory frameworks that firmly root violence within neo-colonial, imperialist, and neoliberal policies (particularly those linked to the U.S. and Israel). In other instances (specially among Middle Eastern scholars), it references national and local cultures and local manifestations of patriarchy as sources of gender-based inequalities and forms of oppression. Al-Ali stresses that as feminist activists and scholars, wherever based, we cannot avoid speaking simultaneously about corruption, political authoritarianism, sectarianism, the instrumentalization of culture, and religion at local and regional levels and various instances of “masculinist restorations”.

“Masculinist restorations” is a term used by Turkish scholar Deniz Kandiyoti, about which she explains that under conditions of neoliberalism, high male unemployment and increasingly precarious labour, as well as the simultaneous increased aspirations and public presence of women, many states engage in crude means to maintain and reproduce patriarchy. Masculinist restorations refer to historically-, regionally-, and locally-specific processes and power configurations that contain authoritarianism, Islamism, and sectarianism, which all intersect with global structures pertaining to imperialism and neoliberal economics.

Al-Ali thinks it appears that it is very difficult for many leftist and supposedly progressive western constituencies to critique, challenge, and resist their own governments on their devastating foreign policies, while simultaneously acknowledging the existence of violent and oppressive local dictators and non-state actors within the Middle East. But these shrill “blind spot” are not merely the prerogative of western scholars and activists; in the context of many diaspora communities, radical uncompromising positions and fervent nationalism can often be stronger if you are miles away and mobilize in relative safety. Al-Ali recalls that during the occupation of Iraq, She was taken aback by Iraqi diaspora activists actively supporting the increasingly sectarian insurgents, who were involved in the killing of Iraqi civilians in their fight against occupation and imperialism more widely.

She finally adds that materially-grounded work is crucial; although representations matter and have material consequences and effects, but we need to make an effort not to abuse and belittle our poststructuralist insights by avoiding messy complex empirically-grounded research. This is not to fall back into naive or positivist notions of empiricism, but to make the case that material realities and the multiple meanings that people of all genders and sexualities attach to them, can not merely be grasped at the level of discourse and representation.

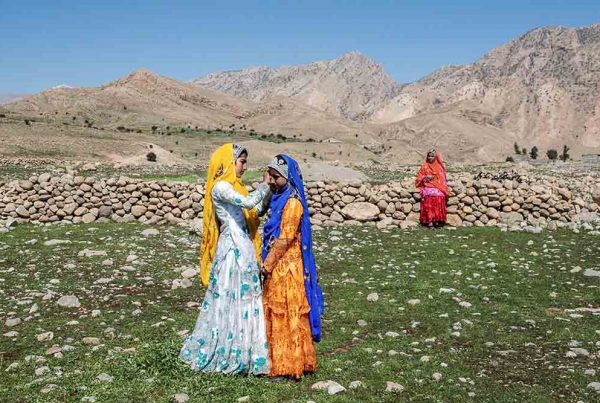

Photo: Alex Webb/ Magnum Photos

«چطور دربارهی خشونت مبتنی بر جنسیت حرف بزنیم»؟ عنوان مقالهای به قلم نادیه العلی استاد مطالعات جنسیت مدرسه مطالعات شرق و آفریقا است که در سال ۲۰۱۶ نوشته شده. اگرچه کار العلی در تحلیل رویکردهای موجود نسبت به خشونت بطور عمده بر جامعهی عراق متمرکز بوده، اما او اعتقاد دارد این موارد برای دیگر کشورهای خاورمیانه نیز صادق است. در این مقاله دکتر العلی به اهمیت اجتناب از رویکردهای دوقطبی خرد و کلان در قبال اَشکال قدرت اشاره میکند که در همتنیده و سازندهی یکدیگرند، و در عین حال نمیتوان هیچ یک را به دیگری تقلیل داد. مثلا در مورد عراق سال ۲۰۱۶، این تنها داعش نبود که دست به اعمال خشونت مبتنی بر جنسیت میزد، بلکه اشغال کشور توسط نیروهای غربی، دولتهای مختلف عراق و نیروهای نظامیشان، شورشیان و گروههای فرقهگرا، گروههای مسلح، و حتی اعضای خانوادهها همگی در وقوع زنندهترین اشکال خشونت مبتنی بر جنسیت نقش داشتهاند؛ از خشونت خانگی و آزار کلامی و جسمی گرفته، تا آزار جنسی، تجاوز، ازدواج اجباری، قاچاق زنان، روسپیگری اجباری، ناقصسازی اندام جنسی زنان و جنایتهای ناموسی از جمله قتل.

العلی استدلال میکند درمیان پژوهشگران غربی، کانون تمرکز عمدتا به آن دسته از چارچوبهای توضیحی تقلیل مییابد که به طور قاطع ریشههای خشونت را در سیاستهای نئولیبرال، امپریالیستی و نواستعماری میبیند (بخصوص سیاستهای مربوط به ایالات متحده و اسرائیل)، و در جبههی مقابل (بخصوص متفکران خاورمیانهای) منحصرا فرهنگ ملی و محلی و مظاهر محلی پدرسالاری را به عنوان منابع نابرابریهای مبتنی بر جنسیت و اشکال مختلف سرکوب معرفی میکنند. العلی تاکید میکند که ما به عنوان پژوهشگران و کنشگران فمینیست، اهل هر کجا که باشیم، نمیتوانیم از پرداختن همزمان به فساد، اقتدارگرایی سیاسی، فرقهگرایی، و ابزاری سازی فرهنگ و مذهب در سطح محلی و منطقهای، و موارد متعدد «تجدیدقوای مردسالارانه» طفره برویم.

تجدیدقوای مردسالارانه عبارتی است که پژوهشگر ترک دنیز کندیوتی به کار برده و در توضیحش میگوید که در شرایط برقراری نئولیبرالیسم، نرخ بالای بیکاری مردان، ناامنی فزایندهی شغلی و همزمان حضور فزایندهی زنان در فضای عمومی، بسیاری از حکومتها برای ابقا و بازتولید مردسالاری، به انواع ابزارهای خشن و بیپرده متوسل میشوند. تجدیدقوای مردسالارانه به اَشکال قدرت و فرایندهای خاص تاریخی، منطقهای، و محلی اشاره دارد که شامل اقتدارگرایی، اسلامگرایی و فرقهگرایی میشود، و همگی اینها در پیوند با ساختارهای جهانی مربوط به امپریالیسم و اقتصاد نئولیبرال هستند.

العلی معتقد است ظاهرا برای بسیاری از تشکیلات چپ و ظاهرا پیشروی غربی، کار دشواری است که هم سیاستهای خارجی مخرب دولتهای متبوعشان را به چالش بکشند و نقد کنند، و هم در عین حال بر وجود دیکتاتورهای محلی و عاملان غیردولتی سرکوبگر و جبار در داخل خاورمیانه صحه بگذارند. اما وجود این «نقطه کور» بینشی تنها منحصر به کنشگران و متفکران غربی نیست؛ در میان بسیاری از جوامع دیاسپورا ـ در حالی که کیلومترها دورتر از سرزمین اصلی هستند و در امنیت نسبی گردهم آمدهاند ـ امکان شکلگیری مواض انعطاف ناپذیر و رادیکال، و ناسیونالیسم پرشور بیشتر است. العلی به خاطر میآورد که در طول اشغال عراق، از مشاهدهی کنشگران دیاسپورای عراق که فعالانه از شورشیان فرقهگرا حمایت میکردند غافلگیر شده بود؛ شورشیانی که در مسیر مبارزهی گستردهترشان با اشغال و امپریالیسم به کشتار غیرنظامیان میپرداختند.

وی در پایان اضافه میکند که اگرچه بازنماییها اهمیت دارند و آثار و عواقب مادی به دنبال دارند، اما کار میدانی و معطوف به دنیای مادی و تجربی، اجتناب ناپذیر و حیاتی است. ما نباید با اجتناب از پژوهشهای پیچیده و پردردسر تجربی و میدانی، از بینش پساساختاری خود سوءاستفاده کنیم و آن را از معنا تهی کنیم. این به معنای بازگشت به دیدگاههای سادهانگارانه یا پوزیویستیِ تجربهگرایی نیست، بلکه توجه به این نکته است که نمیتوان واقعیتهای مادی و معانی متعددی که افراد با هر جنیست و گرایشی به آن واقعیتهای میدهند را تنها در سطح بازنمایی و گفتمان تحلیل کرد.